- Home

- Hardinge, Frances

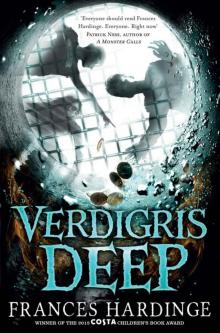

Verdigris Deep Page 2

Verdigris Deep Read online

Page 2

Ryan had been dreaming of the Glass House about three times a year for as long as he could remember. He had never spoken about it to anyone. The truth was, the Glass House dreams left a strange, acrid flavour in his mind that made him want to forget them as soon as possible. Today, however, the lingering memory seemed slightly damper than usual, as if dew had settled on it.

He struggled out of bed and felt his way on to the landing and down the stairs. His father glanced up from his crossword as Ryan stumbled in.

‘Hello. Where are your glasses?’

‘I think Mum’s got them,’ Ryan confessed.

‘Oh, not again.’ His father glanced over his shoulder towards the kitchen door and decided as usual that his voice could travel the distance without him. ‘Anne!’ he shouted.

‘It’s all right,’ Ryan said quickly. ‘Mum doesn’t like to be interrupted when she’s percolating.’

‘Anne,’ his father called out again, ‘your son is running up and down stairs blind and likely to break his neck. We only have one child – can we try not to kill it, please?’

There was the faint hushing of an aerosol can, then Ryan’s mother’s voice: ‘Tell him to put in his contact lenses, Jonathan – he has to get used to them.’

‘Particularly when there’s a danger of a photo opportunity, it would seem,’ called Ryan’s father. Ryan knew that other families took the trouble to enter the same room before talking to one another. His parents, however, thought it perfectly natural to hold conversations from opposite ends of the house at the top of their voices. They carried this conviction with them everywhere they went. ‘Which of your victims are you being interviewed about today, anyway?’

‘Jonathan, don’t call my subjects victims.’

Ryan did try not to think of the people his mother wrote about as victims. Sometimes it was quite hard. She was an ‘unofficial biographer’, which seemed to mean working hard to meet famous people at parties, then writing books about them without asking them first. His mother’s books had shiny lettering on the front, and words like ‘sensational’ and ‘uncompromising’ on the back, and the famous people were usually very unhappy about them. One artist called Pipette Macintosh had been so upset that she had spray-painted their front hedge pink. Ryan’s mother had been very excited about that, partly because it made even more papers want to interview her.

‘Anyway, it’s Curtain Call, wanting to talk to me about the book I’ve started on Saul Paladine. You know, the actor.’

‘Oh, him.’ Ryan’s father was a drama critic, although he had narrowly failed his exams for law school. Ryan thought he would have made a very good lawyer, tall, spruce and handsome in scarlet robes with a crisp white wig, pausing mid-stride to fix the jury with a slow, knowing twinkle. You often got the feeling that he was sharing a clever joke with somebody you couldn’t see, picking the words most likely to amuse them.

‘Delivers his lines like a postman,’ murmured Ryan’s dad. He was thinking theatrical thoughts now, and Ryan had slid out of his mind. Ryan took his cue and slid out of the room, quite literally. The floor of the hallway, living room and kitchen was polished wooden tiles, with grain lines that ran into each other at loggerheads. Ryan had long since discovered that he could skate along these in his socks.

He glided into the kitchen on one foot and had to put a hand out against the wall to balance himself. The wall was clammy with condensation from the coffee-making, and again his dream ran its cold fingers across his mind for a moment. Briefly he thought of a wall of steamed, dripping glass pressed against his palm. His dream-self had, he half remembered, been skimming through the Glass House with a sense of urgency . . .

But he blinked, and the kitchen showed no sign of becoming glass, even if the outlines were a bit fuzzy in places. His mother was standing at a table, pulling and poking at an orchid in a vase as if she was straightening the uniform of a child. Her face was a blur, but he saw the long sweep of her black hair swing and tremble with the brisk little head-shake she often gave when impatient or excited.

‘Mum, can I have my glasses back, please?’

‘You look much better without them.’ The mother shape approached. ‘Let’s have a look at you.’

Ryan could feel his mother’s fingers pulling and poking him around as they had the orchid. He sometimes wondered whether she thought that if she tugged at him for long enough she would end up with something more interesting. But his hair and eyes remained mud-coloured, and no amount of tweaking could make him larger or more impressive.

‘Oh dear, now, what’s that?’ She was turning his hand over and holding it closer to her face. The pad of her thumb rubbed at something between two of his knuckles, vigorously but not painfully. All the same, Ryan found himself wanting her to stop. The skin there felt odd and sensitive. His mother scratched at the place very gently, and he could feel that her fingernail was catching on some slight bump on the skin.

‘Mm. I think it’s a wart or something. Ryan, if you get any more of these, let me know and I’ll take you to a specialist.’ Ryan’s mother liked specialists now she had money. She often showed love by buying Ryan specialists. He sometimes wondered if he would come down on Christmas Day to find one struggling out of wrapping paper with a ribbon festooning his head.

Ryan skated slowly out of the kitchen and along to the back door. Wearing his contact lenses was an easy way to please his mother, but he always felt stubborn about them. He knew he would put them in soon, but he wanted to delay it for a moment. The back door slid sideways, racketing its blind, and the sun patted a hot palm against his face.

He hopped from one warm paving stone to the next, until he reached the little green-painted bench beneath the cherry tree. He squatted on it, facing the back, and then let himself down backwards, until his hands were resting on the grass and he could see the house upside down. Somehow he felt more in control of things when he could turn the house upside down like that.

Josh was the only person he had ever told about this.

When Ryan had joined the Waites Park Primary at age seven there had been so many scary boys. Ryan had ducked his head and blinked behind his glasses and hoped that none of them would notice him. But somehow, by the time the summer field had become too muddy for football and the guttering clogged with fallen leaf mulch, Josh seemed to know his name, and would call it out familiarly.

And then, by the time the hay-fever season returned, it seemed inexplicably that they were friends. Ryan realized this one day when he was hanging upside down from a climbing frame in the corner of the school field. Josh was hanging beside him, and Ryan was telling him about the woman with upside-down eyes, something he had told nobody else.

When Ryan was six he had owned a book of optical illusions. On one page there had been an upside-down picture of a woman’s face. She looked like she’d be pretty and smiling until you inverted the page. Then you got a shock as you registered that the photo had been adjusted so that her eyes and mouth were upside down compared to the rest of her face. The smile was only a smile when the book was the right way up. When you inverted the picture the thing that had been her smile became a terrible clenched-teeth down-turned frown, and her eyes were upside down.

Josh was the only person Ryan had ever told about the way this picture had frightened him. It had shown him that if you looked at things from a new angle they could suddenly become unfamiliar and scary. It became important to see things in as many different ways as possible, so they couldn’t catch you by surprise.

While Ryan had been telling Josh this, he had realized two things. The first was that Josh would not tell everyone and lead them in teasing him about eyes. The second was that Josh was really interested in what Ryan was saying. From time to time he would laugh as Ryan explained that upside-down cypresses looked like a rush of green liquid pouring out of a hole in a field, and that you had to think of people walking around with very sticky feet like flies to stop them falling away into the sky. He had laughed, but then he had

asked more questions and thought about the answers.

‘Cool,’ he had said at last.

Josh understood. Ryan would have worshipped him for that alone. And when Josh occasionally mentioned ‘upside-down eyes’ in passing, he would meet Ryan’s eye to show that he wasn’t teasing, it was just a secret they shared. That gave Ryan a warm, uncomfortable, strangely uneasy sense of pride.

He stood, and teetered slightly as the blood rushed from his head. He padded back to the house and felt his way up to the bathroom.

‘Ryan!’ His mother had obviously heard the creak of the stairs. ‘Coffee saucepans in the bath! Be careful, darling.’

The poinsettia pot which always sat in the bath when it wasn’t in use had been moved on to the flimsy wooden stand with the slender column and the lion’s paws at the bottom. It was so delicate that Ryan knew one day he was bound to knock it over and break everything. It seemed unfair to have to feel guilty about something he hadn’t even done. Ryan moved around the stand very carefully and felt along the window sill for his contact lenses case.

The mirror was clouded with steam from the coffee saucepans, and Ryan could only make out a faint ghost-Ryan craning his head forward to peer. He prised out the first lens, worked out which way up it was and balanced it on the tip of one finger.

Ryan reached out with his free hand, and wiped an arc of glass clear with his sleeve. A streak of the other Ryan’s face became fuzzily visible. It almost seemed to Ryan that there was more steam in the bathroom in the mirror than in the room where he stood, and again the memory of his dream briefly slithered through his thoughts. He beat the memory back, and held his eye open as he dipped his face to his finger and felt the contact lens’s hard strangeness against his eyeball. He straightened, trying not to screw up his face, and for a moment saw clearly out of one eye. He gasped.

The Ryan face that he could see in the streak of clear glass had both eyes closed. The lashes were dark and spiky with moisture, and beneath them tears flowed freely down the face. The eyelids, both upper and lower, were trembling as if they were struggling to open or fighting to stay closed. Then both eyes started to open, and murky water flooded between the lids and bubbled down the cheeks.

Ryan leaped backwards, banging the back of his knee against the edge of the bath and completely losing his balance.

3

The Cavern

Three hours after the mirror incident, Ryan tried to phone Josh. There was a fault on the line, however, so instead he phoned Chelle’s house.

‘Hello?’ Chelle’s voice always sounded even higher and more chirrupy on the phone.

‘Hullo, Chelle.’ It was almost impossible to go straight to the heart of the matter. ‘Chelle . . . I’ve broken the Poinsettia Stand. It’s OK though, cos I fell over at the same time and banged my head and burned my hand on a saucepan of coffee, so nobody minded so much.’

In fact, rather than being angry with Ryan for his clumsiness, his mum had been furious with herself. For a while she had been quite insistent about driving Ryan to casualty in person, she would either cancel the interview completely or leave Ryan’s dad to tell the journalist that she was a terrible mother who liked to boil her own child alive in the bathtub. But seeing the disappointment in his mum’s face Ryan had, of course, persuaded her that the scald was not serious, almost liking how brave he sounded. Eventually she had agreed to go ahead with her interview.

‘Anyway,’ Ryan continued, ‘Chelle – do you think I could come over this afternoon? And can you invite Josh too?’ The mirror incident was something he wanted to discuss face to face. Chelle ran off to ask her mum and returned almost immediately.

‘She says yes. She says it’ll stop me getting under everyone’s feet while Miss Gossamer’s visiting.’

Miss Gossamer had been an old friend of Chelle’s grandmother. Somehow, after Chelle’s grandmother had quietly snuffled herself out of the world, Miss Gossamer had slid into her place within Chelle’s family. Ryan supposed this was probably very good-hearted of Chelle’s parents, but there was something eerie about it, like one of those dreams where a familiar face is replaced with that of a stranger with no explanation. Although Chelle never quite said so, he was sure she felt the same way.

Ryan’s mum still felt guilty enough about the accident to give him a lift instead of leaving him to walk through the park.

Chelle lived in one of a long line of terraced houses. It had tall, thin windows with broad, deep sills which made perfect cat-balconies. Like a lot of old houses, it had an ‘area’, a little square pit in front of the house with steps going down to it, as well as two steps rising to the front door.

The two lowest windows opened on to the area, below street level. At one, Ryan saw Chelle’s face appear. She smiled and waved to him just as the front door opened.

‘Hello, Ryan,’ Chelle’s mother said, scarcely glancing at him before looking towards his mum’s car. ‘Isn’t your mum coming in for a cup of tea?’

‘She has an appointment, um, somewhere, um, quickly.’ His mum was waving from the car with the bright, wide smile she kept for people who made her feel uncomfortable – people like Chelle’s mother, who liked having Ryan’s mum in the house talking about the famous people she met.

‘What a shame . . .’ Chelle’s mother said, then looked down at Ryan absently as if to see whether she had been delivered the right package.

Chelle’s mother’s name was Michelle. As a child she had liked being nicknamed ‘Chelle’, so much so that she had christened her third daughter ‘Chelle’, on her birth certificate. Ryan thought Chelle’s mother looked like the sort of woman who would think this was a good idea.

She had big, vague eyes and a big, vague smile, and was always very busy in the way that a moth crashing about in a lampshade is busy. When she heard that Chelle’s schoolmates were calling her ‘Barnacle-head’ she said things like ‘Aren’t children funny?’

Ryan followed Chelle’s mum into the hall, and the handle of Miss Gossamer’s umbrella in the stand went for him with its parrot beak, as it always did.

Chelle’s house was always so full of sound that Ryan never understood why anybody bothered talking there at all. The radio was on in the kitchen, and the television had been left on in the next room. Upstairs two people were arguing. Somebody seemed to run up or down the stairs every few minutes.

Chelle was waiting for him in the kitchen. Her greeting was lost as the upstairs argument ceased abruptly and her oldest sister, Celeste, thundered down to the front door in her cycle helmet. Someone else, presumably Chelle’s other sister Caroline, retaliated by slamming a door.

Supplied with drinks, Ryan and Chelle descended the narrow stairs to the Cavern.

‘. . . and is it horribly burnt under your bandage?’ Chelle’s nervous, rapid patter only became audible as the door closed behind them. ‘Oh, but don’t show me, I hate scars and things, they make my stomach feel like it’s unpeeling . . .’

Neither of Chelle’s sisters had wanted the basement room, with its mostly lightless window, the annoying pic-pic-pic that emanated endlessly from the light fitting and a creeping yellow edge of damp that drew maps on the ceiling. So Chelle had won the whole wide, chilly, dungeon-like room and loved it with a passion that would have made her sisters jealous had they known.

It was wonderful for secret meetings. Ryan liked looking up and seeing the feet of people passing in the street, not knowing they were being watched from below.

‘. . . and it’s tricky because she always makes me feel like, well, you know what it’s like, when somebody’s watching you and you can feel it like dead leaves down the back of your jumper . . .’

Ryan had no idea what Chelle had been talking about. But the good thing about talking to Chelle was that she never really expected anyone to listen to her properly. When you were used to her you could just let her ramble, and it gave you a nice long space to think about what you were going to say next.

Ryan and Chelle always felt sligh

tly odd together when Josh wasn’t there. In some ways it was easier, because Josh was a firework and you never quite knew which way he was going to explode. When he was absent they talked more freely, and often caught themselves agreeing with each other. Somehow both seemed to become a bit bigger and louder to fill the gaping hole left by Josh. But that chasm was a scary thing to fill. Sooner or later one of them would wonder aloud what Josh would say about something, then they would talk happily about him instead, and the absent Josh would swell up to stop the gap again.

And Ryan knew that soon he would mention Josh’s name, but first he wanted to hear what Chelle thought about something, not what Chelle thought Josh would think.

‘. . . and at first I assumed it was the radio but it turned out to be me and I still don’t know what I was talking about.’ Chelle paused to grimace, and Ryan leaped into the pause.

‘Chelle . . . there’s something I want to tell you. It’s about why I fell into the bath.’

Chelle waited, her own story forgotten.

‘Mum and Dad think it’s because I couldn’t see, and the floor was slippery with steam, but it wasn’t that. Chelle . . . I saw something, and I was jumping back to get away from it. It was when I was trying to put my contact lenses in. OK, my eyes were running, and I didn’t have my glasses, and there was steam everywhere, but I could still see my face in the mirror. Only it wasn’t.’

‘Wasn’t what?’

‘Wasn’t my face.’

The bulb filled the silence with its pic-pic-pic, while Chelle chewed the air and then swallowed.

‘I mean, it looked like me,’ continued Ryan, hearing the pitch of his voice rise, ‘with my hair and my eyelids, only I shouldn’t have been able to see both of my eyelids, should I? My eyes were open. And then when the reflection’s eyes did open, they began pouring water. Not just tears, rivers of water. And the wrong colour. Any kind of a colour is wrong for tears.’

Verdigris Deep

Verdigris Deep